The #1 Reason I Became A Doomer

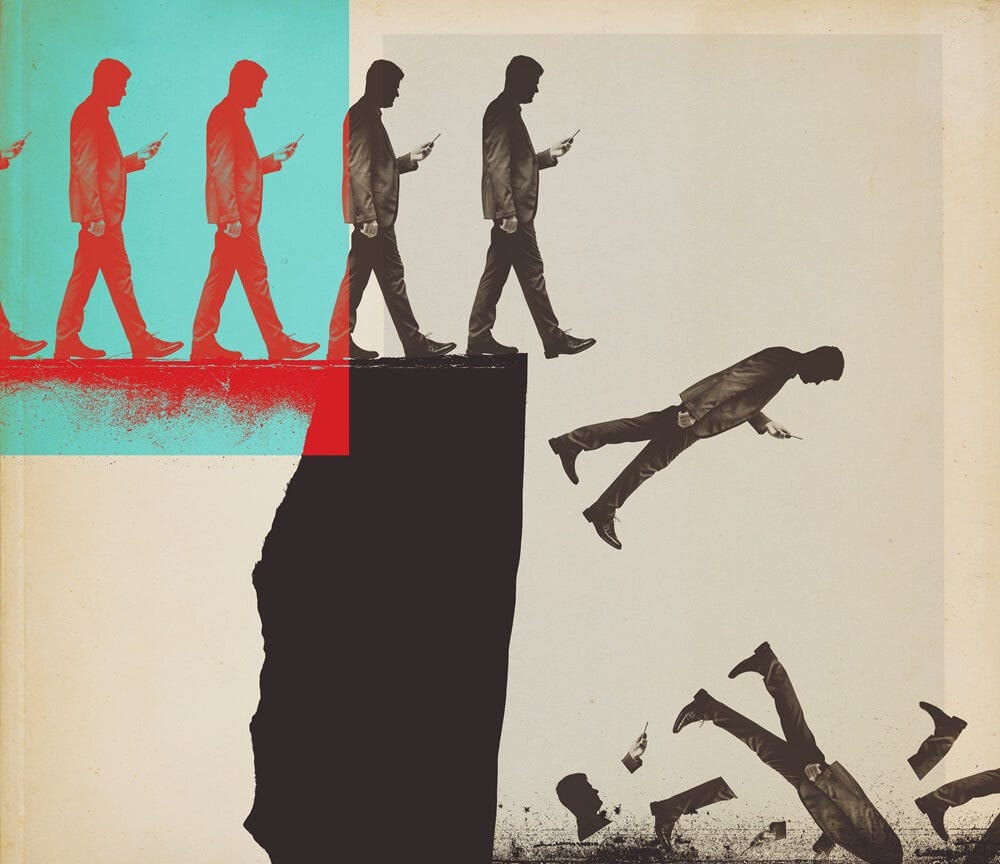

We're not doomed because of climate change, resource depletion, or biodiversity loss. We're doomed because human nature made those things inevitable.

There are many reasons I became a doomer.

Climate change is accelerating and governments aren’t taking it seriously. The sixth mass extinction event is well underway and most people don’t care. Fossil fuels and other crucial resources are running out and most people don’t even know. Pollution in the form of microplastics and forever chemicals are rapidly accumulating in our bodies, lowering sperm counts and causing all sorts of health problems.

And all that is because of overshoot. We’ve already exceeded the carrying capacity of the planet, so it’s only a matter of time before the global population comes crashing down. But overshoot isn’t the main reason I became a doomer. In fact, I became a doomer about a year before I knew what overshoot means.

The main reason I became a doomer is because I realized that the challenge we’re facing is so monumentally large and complicated that humans are incapable of overcoming it.

This idea upsets some people. They say things like, “What about World War II? Look at how the U.S. mobilized the entire nation to help defeat the Axis powers.”

Yea, after they were attacked and only because they had a clear enemy. This time, we can’t simply declare fossil fuels the enemy and stop using them overnight. Doing that would cause civilization to collapse, anyway.

Besides, fossil fuels aren’t the only problem. As I’ve explained before, we would still be headed for collapse even if there were no climate change or pollution because we’re completely dependent on finite resources (forests, aquifers, fossil fuels, rare-earth minerals, etc.) that will mostly be gone in a matter of decades.

Even after learning all this, people still say things like, “What about the Montreal Protocol? Look at how the entire world came together, created an agreement to protect the ozone layer, and followed through.”

Yea, but there’s a big difference between phasing out CFCs and giving up a source of energy that provides 80% of the world’s power, not to mention plastic, fertilizer, and thousands of other products. Even if we could quit fossil fuels, we would just tear up the world’s remaining ecosystems in search of rare-earth metals and other resources.

Despite the enormity of the polycrisis, people still say things like, “We’ll find a way. Look at everything humans have accomplished over the last two centuries: automobiles, airplanes, telephones, computers, and modern medicine.”

Yea, but only because of fossil fuels. Humans have been about as intelligent as we are today for at least 100,000 years, but we only just now managed to invent all these things. Have you ever wondered why?

It’s because starting about 250 years ago, we harnessed a source of energy that, at the time, was practically limitless. We used this energy to build the modern world, but now we have to somehow maintain the modern world while transitioning away from this source of energy. So-called renewables and battery technologies can’t replace everything fossil fuels do for us, and even if they could, we’re already out of time.

To be clear, I’m not saying humans aren’t intelligent enough to deal with the polycrisis. I believe that if everyone on the planet became collapse-aware and committed to saving the human race and as much of the natural world as possible, we could actually pull it off. The population would still decline due to overshoot, but we could turn the decline into a glide instead of a crash.

The problem isn’t a lack of intelligence. Rather, the problem is both psychological and sociological. Humans are incapable of overcoming the polycrisis because they tend to ignore or deny facts that make them uncomfortable.

Recently, I read a fascinating book called Denial: Self-Deception, False Beliefs, and the Origins of the Human Mind by Danny Brower and Ajit Varki. The idea behind the book is that we owe our super-intelligence to our ability to deny death.

At some point in the distant past, our ancestors grew smart enough to become aware of their own mortality. However, this was bad for evolutionary fitness because a fear of death makes one less willing to take risks necessary to ensure the species survives—risks like competing for mates, killing wild animals for food, searching a dangerous landscape for resources, and other activities that could lead to death.

That means too much intelligence is an evolutionary dead end, which could help explain why some of the smartest animals such as wolves, dolphins, elephants, and chimpanzees never got as intelligent as we did. In order to overcome this barrier, humans also developed the ability to deny the reality of death.

That doesn’t mean we can’t acknowledge death on an intellectual level. After all, everybody knows they’re going to die someday. It means we have trouble acknowledging death on an emotional level.

For example, everybody knows that too much sugar, junk food, alcohol, or cigarettes will lead to an early death, but people either refuse to think about it, or they tell themselves that they’re the exception. If they didn’t, they would have to face the pain of giving up unhealthy habits or the pain of knowing their favorite habits are killing them. It’s much easier and less painful to simply remain in denial.

Once you realize that humans have a tendency to deny death, the world starts to make a lot more sense. It explains why so many people believe there’s an afterlife despite a total lack of evidence. It also explains why people deny climate change is real despite the fact that there are decades of evidence and countless studies by thousands of climate scientists from all around the world.

In order to acknowledge that climate change (or peak oil, the sixth mass extinction, etc.) is real, you also have to acknowledge that your lifestyle is contributing to the destruction of the planet and the early death of millions (if not billions) of people. It means that everything the human race has achieved over the last two centuries was all for naught—that all we’ve done is destroy our home and ourselves.

This is a hard pill to swallow for people who believe humans are special. If you believe God created humans and put us here for some divine purpose, it’s hard to accept that we’ve behaved no better than bacteria consuming a piece of fruit. It feels much better to deny the science and continue living like you always have.

So we continue on without changing our ways. As Varki says, “…it is arguable that we are destined ultimately to destroy ourselves as a species – or, at the very least, to continue to cycle between well-developed civilization and catastrophic collapse, never reaching a technological state much beyond what we currently enjoy.” (You can learn more about his theory here.)

Even those who acknowledge that climate change is real tend to deny the reality of the situation. Recently, I read an article in The Guardian called I thought most of us were going to die from the climate crisis. I was wrong. It’s a case study that perfectly exemplifies the human penchant for denial.

The article is an excerpt from a book by Hannah Ritchie called Not The End Of The World. In it, she explains how she used to believe we were heading for a 6°C world and the end of modern civilization, but now she’s changed her mind. So why has she changed her mind? Here are some of the things she says in the article.

“If we stick with the climate policies that countries currently have in place, we’re heading towards a world of 2.5C to 2.9C warming.” She admits that “this is terrible,” but she’s still optimistic because “countries have pledged to go much further.”

I don’t know why she believes countries will stick to these pledges, much less go further. Most countries have been falling short of their climate pledges. And at COP, they can’t even agree to phase out fossil fuels.

Another reason she’s optimistic is because “low-carbon technologies are becoming cost-competitive.” True, but has she ever thought about how we get the materials for those “low-carbon technologies”?

We use diesel to mine and transport the metals. We use coal or natural gas to produce the cement. We use oil to create the plastic. Until all of these things are made without fossil fuels, these new technologies aren’t exactly “low-carbon.”

To get off of fossil fuels, every fossil fuel power plant and internal combustion engine in the entire world has to be replaced by windmills, solar panels, electric vehicles, and more batteries than you can imagine so we can have power when it’s not windy or sunny.

It would take an unbelievable amount of fossil fuels to achieve this. Meanwhile, we’re already committed to 2°C of warming, after which we’ll start triggering irreversible tipping points. As I said before, we’re already out of time.

Later in the article, Ritchie explains how she used to spend countless hours reading about and watching videos of natural disasters. This led her to believe that the frequency and severity of disasters were getting worse. Then she discovered the work of Hans Rosling.

Videos of his lectures taught her that “extreme poverty and child mortality were falling and education and life expectancy were rising.” After doing some research, she learned that “death rates from disasters…have fallen roughly tenfold” over the last century.

Well of course death rates from disasters have fallen. Most of the world now has building codes, early warning systems, emergency response teams, more advanced medical care, access to communication technologies, and much more.

And by the way, all of that is thanks to fossil fuels.

Just because the death rate from disasters has fallen doesn’t mean everything is going to be okay. Yea, it’s a lot easier to survive an earthquake or hurricane than it was a century ago, but that won’t matter if I’m starving to death after simultaneous crop failures across the world.

But Ritchie doesn’t mention that possibility. Instead, she focuses on the fact that annual deaths from natural disasters have been falling for decades. As she says, “When I zoomed out and saw these trends, I felt stupid. I felt cheated.”

Cheated out of what? No one told her to spend so much time reading and watching news about natural disasters. The fact that fewer people are dying in disasters doesn’t change the climate crisis one bit.

Consider this: Deaths from bacterial infections have fallen by over 70% since 1942 thanks to antibiotics. Does that mean we no longer have to worry about bacterial infections?

Of course not! Bacterial infections are still one of the leading causes of death, and thanks to the overuse of antibiotics, we are now entering a post-antibiotic world where infections will kill more people than cancer. Just because a trend is going down doesn’t mean it will keep going down forever.

Later, she offers another reason for hope when she says, “the world has already passed the peak of per capita emissions. It happened a decade ago. Most people are unaware of this.”

That’s great, but global emissions are still rising. It doesn’t matter if per capita emissions are going down if overall emissions are still going up. But Ritchie is “optimistic we can peak global emissions in the 2020s.”

She could be right about that, but just because our emissions stop rising doesn’t mean the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere stops rising, too. As our emissions go down, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere will keep going up, only at a slower rate.

She goes on to explain how thanks to improvements in technology and energy efficiency, her carbon footprint is less than half that of her grandparents’ at her age. Maybe so, but there are also three times as many people in the world today, so we’re still burning more fossil fuels than ever before.

At one point, she says, “The notion that we need to be frugal to live a low-carbon life is simply wrong.” That really depends on what she means by “low-carbon.” As a Westerner, her carbon footprint is likely much higher than the global average, meaning that if everyone lived like her, the planet would be much warmer already.

Even if everyone in the world lowered their carbon footprint to zero and we stopped emissions overnight, the CO2 that’s already in the atmosphere would keep warming the planet until the Earth reaches a new energy balance.

According to James Hansen, one of the most highly-respected climate scientists in the world, the amount of CO2 already in the atmosphere would lead to 10°C of warming over the next few centuries, and as much as 6 or 7°C in one century. And that doesn’t include future emissions.

There’s something else that would happen if we stopped emissions overnight: Global temperatures would spike. Few people know this, but a small percentage of sunlight is blocked by pollution (especially aerosols) from fossil fuels. Thanks to this pollution, the planet is about 0.4°C cooler than it otherwise would be.

If we were to stop burning fossil fuels, the average global temperature would spike to nearly 2°C. But as I already explained, we can’t just stop burning fossil fuels overnight, so at this point, at least 2°C of warming in the next decade or two is unavoidable, at which point we’ll have triggered even more tipping points.

On top of that, many of the climate impacts we’re seeing at a mere 1.3°C of warming weren’t supposed to happen for decades. That means 2°C is probably going to look a lot worse than expected.

Ritchie is obviously smart enough to understand all this, yet she says, “Leaders no longer have to make the difficult choice between climate action and providing energy for their people.”

This is absurd. Even if wind and solar keep getting cheaper, we still need to cut our energy usage as quickly as possible. And that will be really hard to do if we’re using fossil fuels to build enough renewables, batteries, and EVs to replace the entire planet’s energy infrastructure and transportation system.

I don’t mean to attack Hannah Ritchie. I’m sure she’s a great person, and I think she truly believes what she’s saying, but that’s the problem. She was so terrified of climate breakdown that she convinced herself there’s still hope. She simply couldn’t handle the horrifying reality that billions of people are going to die an early death, so she found a way to deny it.

And now she’s telling people that we can maintain modern civilization and stop climate change. That we can have our cake and eat it too. By doing this, she’s only making things worse. Books and articles like hers make it easier for people to deny reality and continue their carbon-based lifestyles without feeling guilty or afraid.

If climate change had a simple fix—like the Montreal Protocol—we would have done it already. But there is no fix for climate change. At best, we could slow it down, but that would require most people to drastically lower their standard of living—something like a permanent Great Depression. And since that is unthinkable, people deny the truth and tell themselves everything will be okay.

That’s why I became a doomer. I realized that people are unwilling to make the changes necessary to avoid collapse, so they deny reality and cling to false hope. For decades, scientists have been warning us that we have to act as soon as possible, yet all we’ve done is the bare minimum. I don’t see any signs of that changing.

Humans simply didn’t evolve to handle a situation like this, and now there is research confirming it. According to a study by the University of Maine, certain features of human evolution could be stopping us from solving environmental problems. Researchers looked at how sustainable human systems emerged in the past, and they found two patterns:

Sustainable systems emerge only after groups have failed to maintain their resources. But today, if we don’t learn our lesson until after we’ve exhausted our resources, it will be too late. We won’t have the option to relocate to a new area because climate change and resource depletion are happening everywhere.

Systems of environmental protection tend to address problems within societies, not between societies. To slow down climate change, we would need worldwide regulatory, economic, and social systems. Without that, individual countries and regions will focus on their own problems and could even go to war with their neighbors for resources.

As the lead author, Tim Waring, said, "This means global challenges like climate change are much harder to solve than previously considered…It's not just that they are the hardest thing our species has ever done. They absolutely are. The bigger problem is that central features in human evolution are likely working against our ability to solve them.”

In other words, the traits that were beneficial in natural selection and allowed humans to colonize the entire planet are counterproductive in a global civilization. Our technological progress has far outpaced our emotional maturity, and now we’re like monkeys playing with blowtorches. Eventually, we’re gonna burn everything down.

And like I said before, even if we were capable of facing reality and working together on a global scale, it’s already too late to prevent a climate catastrophe. Maybe we could slow it down, but it wouldn’t prevent the collapse of modern civilization because it’s already too late.

So what now?

Instead of lying to ourselves and repeatedly claiming that “there is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a livable and sustainable future for all,” we should just admit that we fucked up and deal with the consequences.

Once we do this, we can stop trying to sustain an unsustainable civilization and instead focus on adapting to a warmer world and minimizing the pain as much as possible. It will still be hell, but I believe we could make a significant difference if we tried. For example, maybe the global population could drop by a billion per decade instead of a billion per year.

But right now, it looks like we’re heading for a rather sudden and uncontrollable collapse in the next decade or two. When that happens, we’re going to see the worst of humanity. Once all the food is gone, people are going to turn on each other, and it’s gonna get ugly. However, I believe we’ll also see the best of humanity. We’ll see acts of heroism, bravery, and sacrifice like never before.

I don’t know how my life is going to end, but I’d rather go out helping people than hurting people. As Michael Campi wrote, “What if we did things not for points, or rewards, or recognition but for the sheer joy that comes from making someone else happy for a moment? That’s all that’s left to us.”

He’s right. We’ve already lost everything else. All we can do now is wait for the end and try to be a source of comfort and strength for those around us.

Thank you,Mr Urban. I think we should form groups of neighbors for mutual aid and support.

https://climatecasino.net/2023/06/on-being-a-doomer/

Eliot Jacobson speaks for me with this article

On Being A Doomer